Blue Pigments in Islamicate Manuscript Painting: Materiality and Courtly Practice

In the manuscript traditions of the Islamicate world, blue pigments held both material significance and visual prominence. Scientific analysis of Safavid and later Persian manuscripts demonstrates that ultramarine, derived from lapis lazuli, was the principal blue pigment, valued for its intensity and cost. Raman microscopy studies of sixteenth‑ and seventeenth‑century Persian manuscripts have identified ultramarine consistently alongside other palette staples, while organic dyes such as indigo also appear but less frequently as the dominant blue.¹

In Safavid Iran the court workshop inherited and refined a long tradition of miniature painting that drew upon Timurid precedents and local innovations. Persian painting of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries was characterised by a luxuriant palette in which certain colors, most notably blue, were not neutral additives but material markers of value. The mineral pigment derived from lapis lazuli, processed into natural ultramarine, was valued for its capacity to produce luminous and deep tones. It appeared in both figural and decorative contexts, often juxtaposed with gold leaf and bright reds, creating a visual counterpoint that emphasized the depth of skies, textile patterns, and architectural canopies. In scholarly surveys of the Persian tradition it is clear that the material and visual richness of Persian illumination was inseparable from the value of the pigments themselves. Scholars note that the most prized miniatures of the Safavid courts show careful and selective deployment of ultramarine in conjunction with other high status colors in manuscripts intended for royal patrons.¹

Ptolemaic Vase Fragment with Ultramarine Glaze

Thin, flat fragment of a vase (possibly mould-made) featuring a rich ultramarine blue glaze on the exterior. The interior shows no remaining glaze, suggesting it may have been part of a closed vessel or that glazing chipped off over time. Excavated at Naukratis, Lower Egypt, this Ptolemaic-period object (3rd–2nd century BCE) exemplifies the use of vivid ultramarine in Egyptian decorative arts.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Record via the British Museum: Eg.Inv.3577.4.

The use of organic blues, such as indigo, also forms part of the broader material vocabulary of Persian painting, though with a slightly different technical and aesthetic function. Whereas ultramarine derived from lapis commanded high value and was often restricted to emphasis zones within the composition, indigo and its derivations provided a range of softer blue tones that could be mixed with white pigments for lighter hues. Technical studies of manuscript pigments identify both ultramarine and indigo in works of the period and demonstrate how artists combined these with white lead to achieve pastel blues for drapery and backgrounds.² Such coloristic practices reflect a sophisticated workshop knowledge of materials and tonal modulation that underwrote the production of luxurious manuscripts.

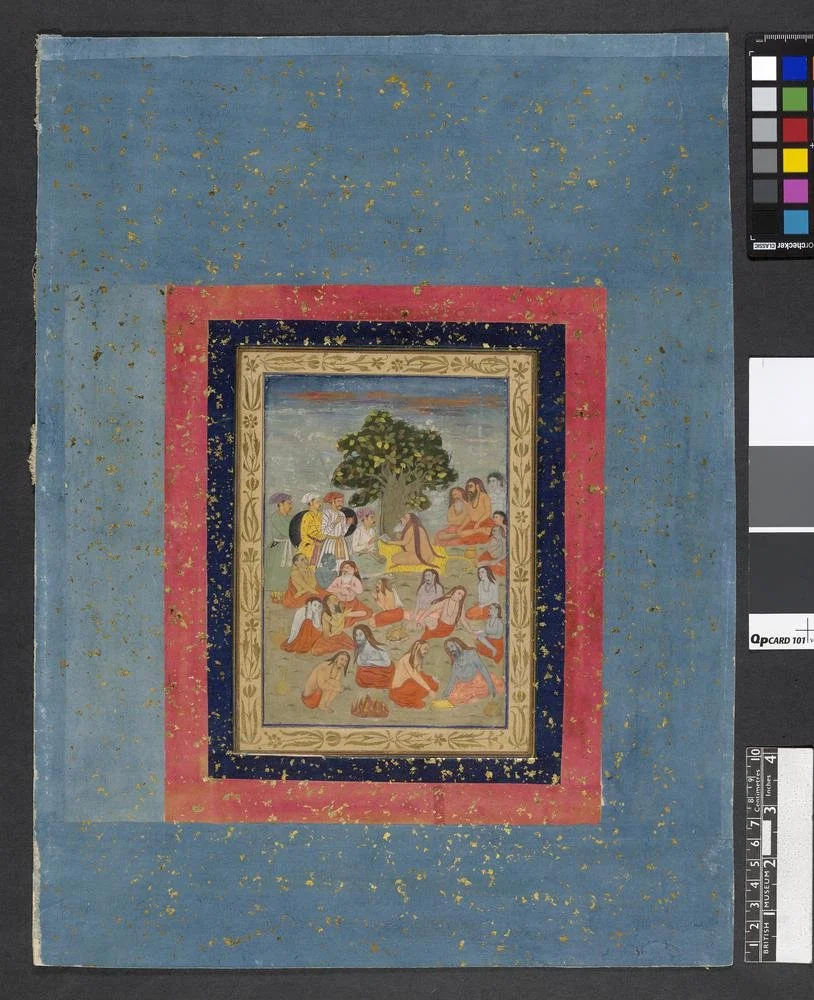

A Gathering of Ascetics

Miniature painting from a Rajasthani album (c. 1750–1800) depicting ascetics under a tree engaged in discussion around small campfires. Clad in orange robes or bare, some ascetics have blue-toned bodies smeared with ash (vibhuti), indicating their Saivite affiliation. One grey-bearded ascetic on a tiger skin hands a petition to a seated nobleman, attended by three armed attendants. Unfinished areas reveal uncoloured figures, offering insight into the painting process. Likely produced by a Mughal artist in Rajasthan, possibly Bikaner.

British Museum, Registration number 1999,1202,0.3.8.

In the Mughal context the imperial ateliers of Akbar and his successors assimilated and transformed Persian visual paradigms, producing a hybrid courtly painting style that maintained the centrality of blue within its palette while developing distinct narrative and naturalistic emphases. Mughal painting scholars have emphasized that under Akbar the workshop expanded the scope and scale of illustrated manuscripts, commissioning ambitious projects such as the Hamzanama and the Akbarnama, which integrated figural narratives with richly coloured backgrounds.³ Although the relative use of particular pigments can vary according to individual manuscripts, the continued presence of deep blues in Mughal court painting reflects both inherited Persianate conventions and localized aesthetic priorities within the Indian imperial setting.

The material presence of blue in Mughal manuscripts is inseparable from the institutional context of the court workshop, where painters trained in Persianate technique worked alongside indigenous artists. The Mughal emperors regarded the craft of painting as a key component of imperial representation and invested in the procurement and preparation of pigments as part of the workshop infrastructure. In this milieu, blue tones served both to articulate pictorial space and to convey the prestige of the illustrated book as an object of elite cultural capital. The stability of certain blue pigments, particularly lapis‑derived ultramarine, ensured that the visual impact of these tones remained vivid across centuries of patronage and collection.

Thus, the use of blue in Islamicate manuscript painting reflects more than decorative preference. It speaks to the interconnected histories of Safavid and Mughal visual cultures, the economics of pigment acquisition, and the imperial aesthetics of courtly book arts. The persistence of deep blues from the manuscript pages of Isfahan to those of Agra and Lahore underscores the centrality of material colour traditions in shaping the visual languages of early modern Islamic courts.

Footnotes

¹ Sheila R Canby, Persian Painting: The Arts of the Book and Portraiture (London: British Museum Press, 1993).

² Manuscript pigment studies identify ultramarine and indigo in Persian works; see Michael Khorandi, PhD diss., Investigation of colour materials applied in ... (University of Hamburg, 2025).³ J M Rogers, Mughal Miniatures (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999) and Milo Cleveland Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987).

Bibliography

Canby, Sheila R. Persian Painting: The Arts of the Book and Portraiture. London: British Museum Press, 1993.

Khorandi, Michael. Investigation of colour materials applied in ... PhD diss., University of Hamburg, 2025.

Rogers, J M. Mughal Miniatures. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.