Crafting the Manuscript: Materials, Labor, and Aesthetics in Islamic and Indian Book Production, 1400–1800

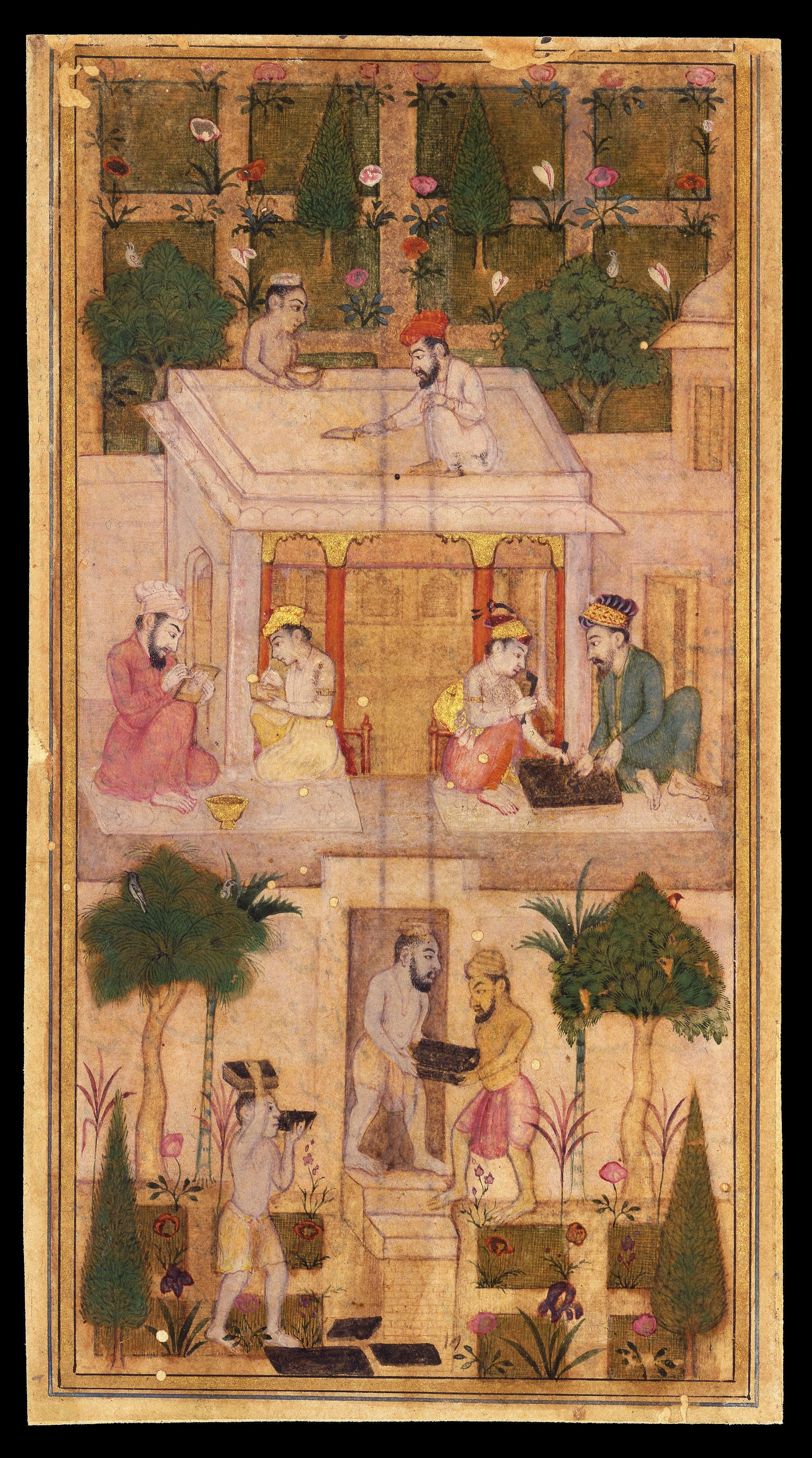

Miniature, “Making Books in a Garden.” India, Deccan (Aurangabad?), 17th century. Leaf 15.9 × 8.6 cm, Inventory no. 45/1980. The David Collection, Copenhagen.

Crafting the Manuscript: Materials, Labor, and Aesthetics in Islamic and Indian Book Production, 1400–1800

Between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, manuscript production across the Islamic and Indian worlds constituted a sophisticated, multi-stage craft tradition integrating material technologies, artisanal specialization, and aesthetic theorization. This short essay outlines the principal stages of manuscript manufacture from paper production, preparation of inks and pigments, calligraphy, illumination, binding, and circulation.

1. Paper and Substrate Technologies

Although parchment remained in sporadic use, the period 1400–1800 was dominated by Islamic handmade paper, often produced in Khurasan, Samarqand, Kashmir, and the Deccan. Rag-based paper (typically flax, hemp, or cotton fibers) was pulped, molded on a screen, and pressed into sheets. What distinguishes Islamic paper technologically is sizing and burnishing:

Sizing: Sheets were saturated with wheat starch or animal glue to reduce absorbency, permitting crisp calligraphic strokes.

Burnishing (āhangarī): Using an agate or glass burnisher, artisans polished the sheets until they achieved a glistening, semi-reflective surface. This also densified the fibers, giving the page its characteristic hardness.

By the early Mughal period, advances in ṭilā kāghaz (“gold paper”) and colored papers (pink, azure, pistachio) reveal an increasingly experimental material culture tied to courtly tastes.

2. Inks, Pigments, and the Chemistry of the Scriptoria

Bookmaking relied on complex ink recipes:

Carbon inks (midad): Produced from lampblack mixed with gum arabic; valued for permanence and depth of black.

Iron-gall inks: Common in bureaucratic contexts, though less stable over time.

Colored and metallic inks: Gold ink (made from powdered leaf suspended in gum) and red cinnabar or minium inks were used for headings, rubrics, and ruling.

Pigments for illumination drew on a global supply chain: lapis lazuli from Badakhshan, verdigris, orpiment, and later Prussian blue. Mughal workshops, in particular, developed sophisticated pigment grinding and washing techniques (safīd-kārī) to achieve ultrafine particles.

3. Scribal Practice and Calligraphic Aesthetics

The calligrapher (kātib or khattāt) occupied the highest status within the manuscript atelier. Training followed a master–disciple model, emphasizing:

Pen-cutting (qalam-tarāshī): The reed pen was trimmed to produce nib angles specific to script style—naskh, nasta‘liq, shikasta, ta‘liq.

Ruling and layout: Pages were ruled with a misṭara (ruling board) to ensure even baselines and margins. In Persianate ateliers, the nasta‘liq script required delicate proportional systems governed by canonical treatises such as those attributed to Mir ‘Ali or Mir Imad.

Copying was often a collaborative, serial act: a single manuscript might involve several scribes, each responsible for specific gatherings (quires), a practice especially common in large Indo-Persian epics and genealogical chronicles.

4. Illumination, Ornament, and the Visual Architecture of the Page

Illumination (tadhhīb) was typically undertaken by a separate specialist, the muzahhib. It involved:

Headpieces (sarlawḥ or ‘unwān): Intricate gold-and-lapis panels introducing major text divisions.

Marginal decoration: Rosettes marking verse divisions, cloud-bands, and vegetal scrolls influenced by Timurid, Safavid, or Mughal aesthetics.

Page design: Interplay of text blocks with margins painted in gold-sprinkled (zer-afshān) patterns or illustrated with flora and fauna.

In Mughal India, a unique synthesis of Persian, Indic, and European visual vocabularies emerged. Albums (muraqqa‘at) combined calligraphy, painting, and decorated margins into curated aesthetic objects.

5. Binding: Structure, Ornament, and Longevity

Bookbinding in Islamic and Indo-Persian traditions diverged markedly from European models:

Boards: Laminated pasteboards or thickened paper layers rather than wooden boards.

Sewing: Linked-stitch sewing across supports, often with a distinctive Islamic chevron endband (zanjīrah).

Covers: Leather or lacquered paper (in Safavid and later Mughal ateliers), decorated with stamped medallions, pendants, and cornerpieces.

Flap (muraqqa‘a/ghilāf): The envelope-style fore-edge flap, both protective and aesthetic, is a hallmark of Islamic bindings.

Bindings could be commissioned separately from the manuscript and were sometimes replaced as objects passed between courts.

6. Production Contexts and Patronage

Manuscripts were not only textual objects but symbols of sovereignty and intellectual refinement. Key production environments included:

Imperial ateliers (kitābkhānah): Highly stratified workshops in Timurid Herat, Safavid Isfahan, Ottoman Istanbul, and Mughal Delhi/Agra. These workshops integrated scribes, illuminators, painters, paper-makers, pigment specialists, and binders under court supervision.

Madrasa and Sufi networks: Produced devotional writings, commentaries, and practical texts with fewer luxury components but consistent scribal rigour.

Market-based production: Especially in cities like Isfahan, Shiraz, Lucknow, and Lahore, professional scribes produced manuscripts for urban patrons, creating hybrid styles and greater material variation.

7. Circulation, Use, and Afterlives

After production, manuscripts lived dynamic social lives:

Annotation culture: Readers added glosses (ḥāshiya), ownership marks, and marginalia, creating multi-generational intellectual palimpsests.

Repair and rebinding: Manuscripts were regularly restored; folios could be replaced or remounted in albums.

Collecting: By the 17th–18th centuries, elite bibliophilia expanded, and manuscripts functioned as diplomatic gifts and markers of cultural prestige.

This painting above is a rare visual articulation of the sequential processes involved in manuscript production within an Indo-Persian or Mughal atelier. The vertical organization of the scene guides the viewer through the layered divisions of labour that structured early modern bookmaking. In the lower register, workers handle what appear to be freshly treated paper sheets or paper boards, an activity that corresponds to the preliminary phases of sizing, drying, and burnishing described in the essay. These foundational tasks created the polished, resilient writing surfaces characteristic of manuscripts produced across Islamic and Indian centres from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century. The middle register depicts scribes and workshop specialists engaged in writing, tool preparation and pigment handling. Their careful postures and the measured proportions of the writing surfaces evoke the disciplined geometry that governed naskh and nastaʿlīq scripts. The scene conveys the hierarchical world of the kitabkhana, in which calligraphers worked alongside illuminators and preparatory artisans, each contributing a discrete skill that shaped the eventual coherence of the manuscript.

The upper register places these technical processes within a cultivated garden setting, a visual strategy that carries both literal and symbolic significance. Mughal ateliers were frequently embedded within palace or garden complexes, and artists often drew upon horticultural motifs to express ideals of cultivation, refinement and intellectual fertility. In this image, the presence of flowering plants and ordered trees frames the preparation of pigments and the refinement of materials, implying that the formation of a manuscript was imagined as a process of careful tending and growth. The miniature therefore operates on two levels. It documents the procedural steps outlined in the essay, from material preparation to calligraphic execution and decorative work, while simultaneously presenting manuscript production as a disciplined and aesthetically elevated practice.

Thus, the making of a manuscript in the Islamic and Indian worlds between 1400 and 1800 was a materially complex and intellectually rich process. It entailed deep technical knowledge such as paper chemistry, pigment preparation, calligraphic geometry as well as being aware of the courtly aesthetics, artisanal hierarchy, and transregional exchanges in a diverse and dynamic environment. As physical artefacts, these manuscripts encode the movement of ideas, people, and technologies across a vast cultural landscape, revealing bookmaking as both an artistic pursuit and a political-cultural act.