A Late Sixteenth-Century Copy of the Divan of Urfi Shirazi

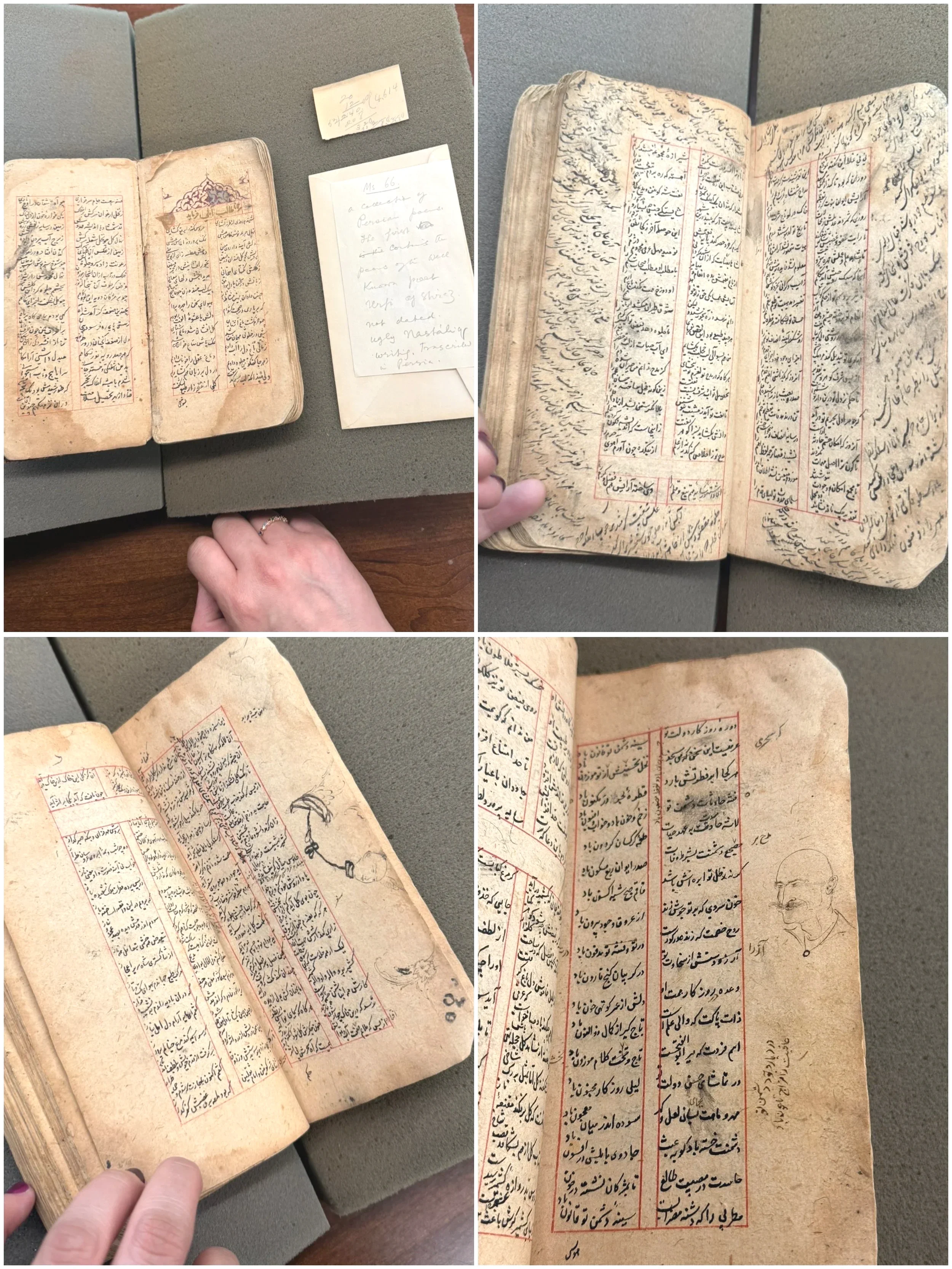

This manuscript is a late sixteenth century copy of the Divan of the celebrated Safavid poet Urfi Shirazi who lived from 1555 or 1556 to 1590 or 1591. Urfi was an influential figure in the Persian literary tradition whose career flourished at the Mughal court. The codex contains a range of poetic forms including qasāʾid, muqaṭṭaʿāt, rubāʿiyyāt, the Javāb i Makhzan, the Sāqī nāmah, and a qasīda in praise of Mawlānā ʿAmīdī. A later hand has added section titles and marginal annotations. The manuscript begins abruptly which suggests the possible loss of initial folios.

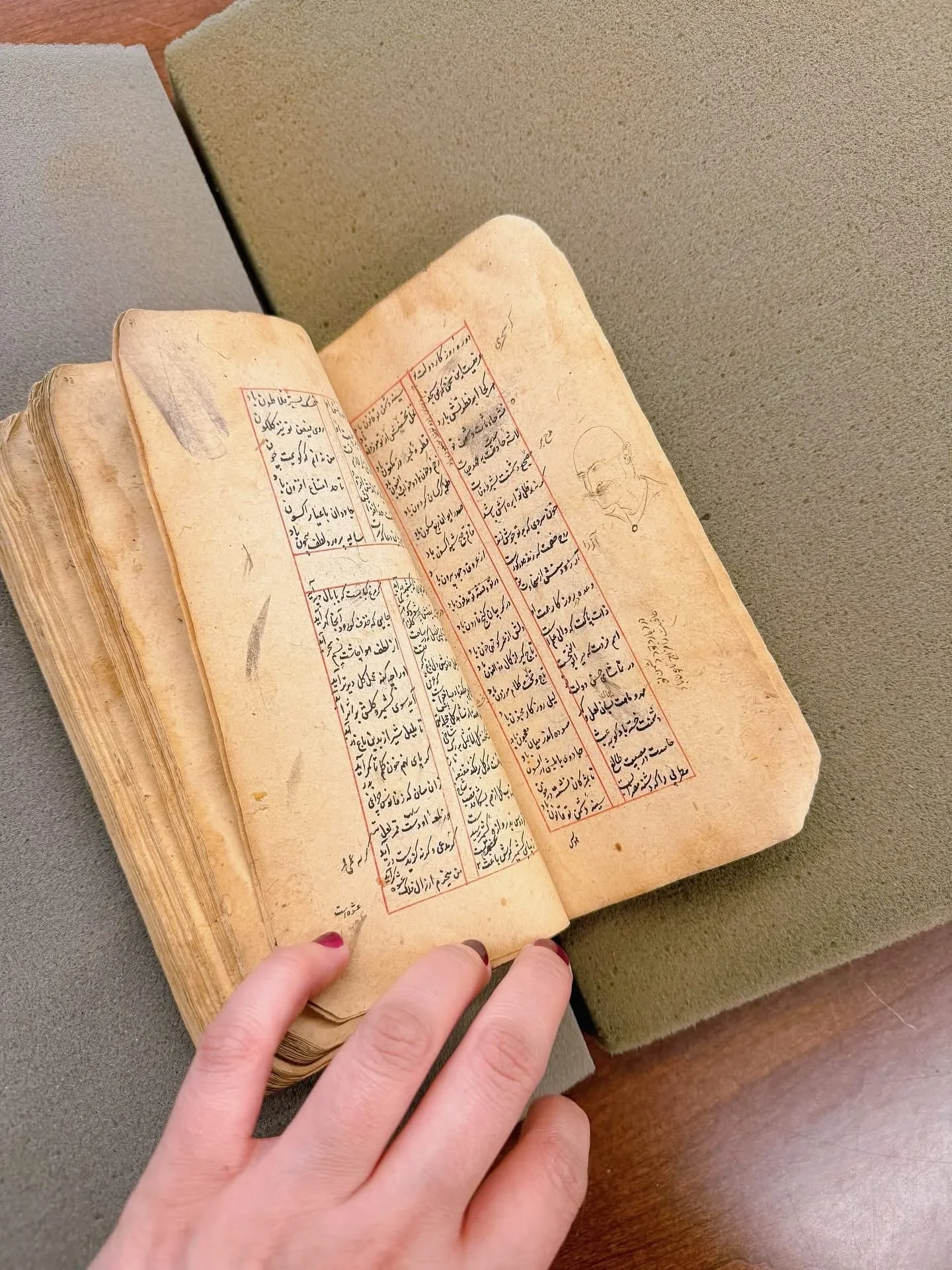

Several monochrome foliate headpieces and marginal doodles which were likely added by a later reader decorate the text. These features reflect continued engagement with the work after its original production.

Manuscript: Rendel Harris 66, Divan of Urfi Shirazi

Date: 1592 to 1593 CE, 1001 AH

Language: Persian

Place of Origin: Possibly India or Iran

Material: Laid paper

Extent: 220 leaves, 185 by 90 millimeters, written area approximately 150 by 60 millimeters

Script: Nastaʿlīq in black ink with rubrication in red

Binding: Reddish leather over thin pasteboard with blind tooled frame and significant water damage

Physical Features:

The text is arranged in two columns of nineteen lines, framed and ruled in red ink. Catchwords appear on the verso of each leaf. Modern pencil foliation has been added in the upper left recto. The reddish leather binding is water damaged and features blind tooling along the frame.

Provenance:

The manuscript passed through several hands before entering the Haverford collection. Former owners include Muhammad Salim as noted on folio 129 verso and Hasan Naqqash Isfahani Muhammad Ali as noted on folio 140 verso. It was later acquired by J. Rendel Harris whose collection now resides at Haverford College.

Scholarly Notes:

This copy is significant for its possible origin in India which if confirmed would place it within the cultural exchange between Safavid Iran and the Mughal court during the late sixteenth century. The marginalia and later additions also provide insight into the manuscript’s post production life showing how Persian poetic works continued to be actively read, customized, and aesthetically enhanced by successive owners.

The informal marginal drawings, such as the face of a mustached man and a figure on a noose, neither of which appears to relate directly to the text, were likely added by anonymous later readers rather than the original scribe. For scholars, these seemingly unacademic additions are important because they document how the manuscript was handled, personalized, and emotionally engaged with over time, offering rare insight into the everyday human interactions that shaped the afterlife of Persian literary works beyond their original production. Such marginalia are often interpreted as evidence of reader response, moments of contemplation, boredom, or emotional reaction, and they complicate the idea of manuscripts as fixed or purely authoritative objects. When manuscripts enter libraries or museum collections, these marks become part of the material record, allowing historians to reconstruct patterns of ownership, use, and interpretation that are otherwise absent from formal colophons or textual commentary. In this way, non-textual annotations and drawings contribute to a broader understanding of manuscript culture as a dynamic process in which meaning was continually negotiated by successive readers across time and place.